We hear the word stigma a lot. People might say, “There’s a stigma around asking for help,” or “They felt stigmatized.” But what does that really mean, especially when it comes to things like food insecurity?

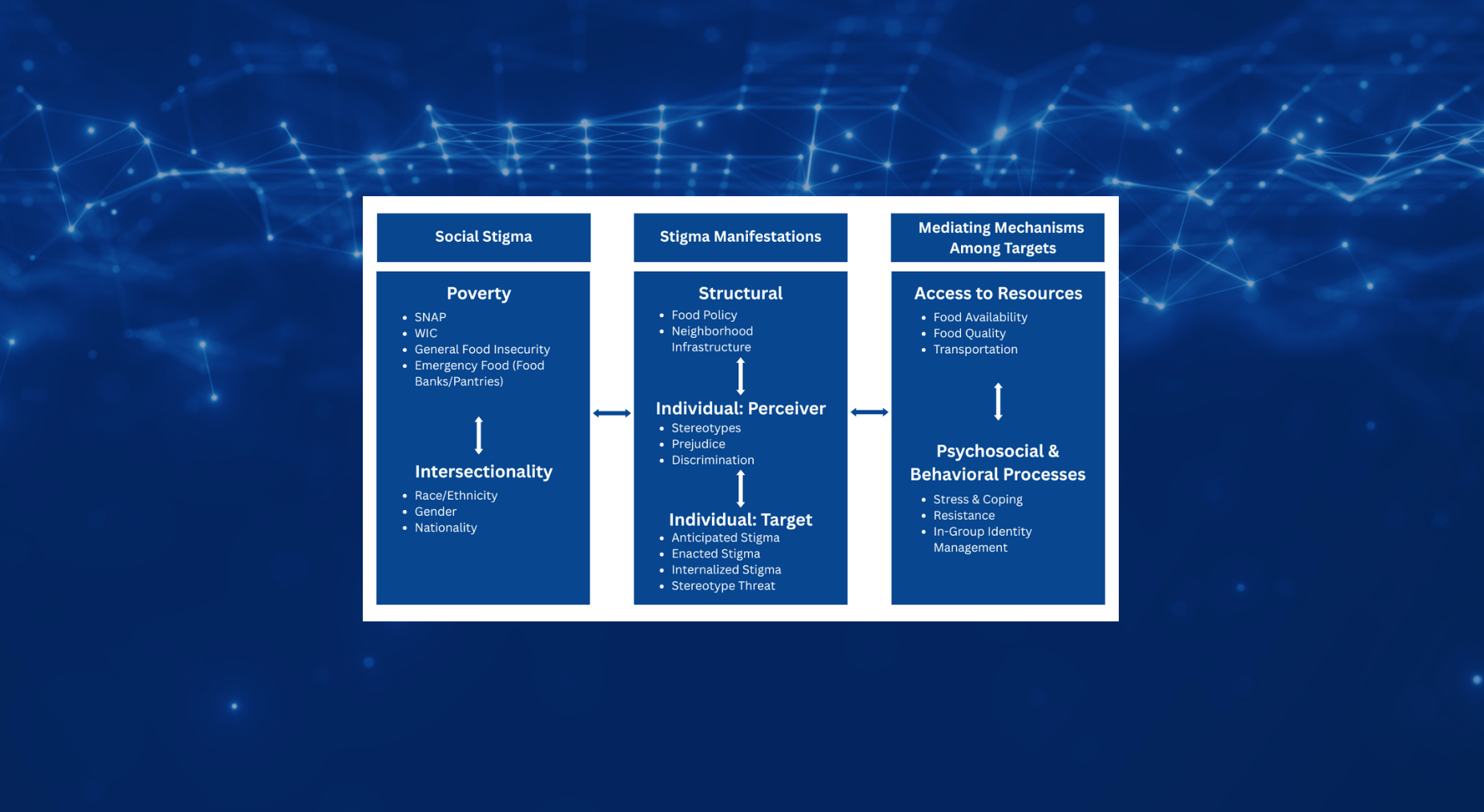

In everyday conversation, stigma usually means someone being judged or treated unfairly. But in science and public health, stigma is more than just one person being treated badly. It also includes unfair systems, public attitudes, and even how people feel about themselves. Let’s break it down using the Stigma and Food Inequity Framework, a tool researchers use to understand how stigma shows up in people’s lives and makes it harder for them to get the food they need.

- Structural-Level Stigma

This kind of stigma is built into policies, rules, and systems.

It’s not about one person’s actions—it’s about the way things are set up.

Example:

A food pantry that requires a lot of personal information to get help or a government program with complicated paperwork that makes it hard to apply.

- Individual-Level Stigma

This form of stigma is personal.

It shows up in relationships with others, and even in the way someone sees themselves. It includes two parts (target and perceiver).

- Target Stigma – What people experience when they are stigmatized

This is the stigma that directly affects people who are food insecure. It shows up in three ways:

- Anticipated Stigma

The fear that others will judge you.

Example: Avoiding a food pantry because you’re afraid people will think less of you.

- Enacted Stigma

When you’re actually treated unfairly or shamed.

Example: A cashier makes a rude comment when you pay with food benefits.

- Internalized Stigma

When you start to believe the negative thoughts others say about you.

Example: Feeling like a bad parent because you need help feeding your family—even though food insecurity is not your fault.

- Perceiver Stigma – What people believe about others

This includes the thoughts and behaviors of people who hold stigma toward others. It has three parts too:

- Stereotypes

The assumptions people make about other groups.

Example: Thinking that people who use food stamps are lazy or irresponsible.

- Prejudice

The negative feelings people have toward others because of those stereotypes.

Example: Feeling annoyed or resentful toward people who receive food assistance.

- Discrimination

The actions that come from stereotypes and prejudice.

Example: Refusing to donate to a food pantry because you don’t believe people “deserve” help.

Why This Matters

Stigma is more than just feeling bad. It can actually stop people from getting the help they need, which makes food insecurity worse. It also adds to bigger problems, like health and income inequality—especially for people who are already facing other kinds of discrimination. Understanding stigma helps us create better systems and more compassionate support for everyone.